Mission & History

Founded in 1925, the Kosciuszko Foundation promotes closer ties between Poland and the United States through educational, scientific and cultural exchanges. It awards up to $1.7 million annually in fellowships and grants to graduate students, scholars, scientists, professionals, and artists, and promotes Polish culture in America. The Foundation has awarded scholarships and provided a forum to Poles who have changed history.

How it all began, the education and vision of Stephen Mizwa

Szczepan Mierzwa was born to a peasant family on Nov. 12, 1892, in Rakszawa, a Polish village occupied by Austria-Hungary. At age 12, he heard about Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who championed peasants’ rights and “stuck his neck out when there was fighting in a big country called America.” In 1910, the 17-year-old Mierzwa boarded a German steamship, the SS Princess Irene, and slept on a bunk of old straw in steerage. Without speaking English, he disembarked at Ellis Island and headed for Northampton, Mass., where Polish immigrants helped him find work. Americans knew him as Stephen Mizwa, who made wooden boxes, peeled potatoes, and washed dishes while studying at night. He earned a scholarship to Amherst College and later completed a master’s degree at Harvard University. In 1922, Mizwa was named associate professor of economics at Drake University.

While teaching at Drake, Mizwa read an article by the President of Vassar College, Dr. Henry Noble MacCraken, who returned from Europe and praised Krakow’s Jagiellonian University. Mizwa visited MacCracken, and they discussed setting up a cultural exchange program between Poland and the United States and raising money for scholarships.

Mizwa later recalled: “All the principles of Economics, Money, and Banking courses that I was teaching did not tell me how to ask people for money for which they would not receive anything in return – except a promise that their donations would help some young people that they did not know.” Yet Mizwa did just that. He bought a Corona portable typewriter and used two fingers to peck out letters asking for money to start the Polish-American Scholarship Committee. The first donation was $5, and soon Polish Americans began contributing to the fund.

Poland regained its independence after World War I. Władysław Wróblewski, a former Jagiellonian University law professor and Prime Minister of Poland’s interim democratic government, was sent to Washington, D.C. as Poland’s representative. Wróblewski was respected among Poles, so Mizwa asked him to become President of the scholarship committee.

To inspire confidence in his endeavor and prove that it was a true American-Polish committee, Mizwa convinced Dr. MacCracken and an industrialist, Samuel Vauclain, President of Baldwin Locomotive Works, to serve as vice-chairs. Vauclain had sold locomotives to Poland when Ignacy Jan Paderewski was Prime Minister.

A “Living Memorial” to Tadeusz Kosciuszko

The idea paid off, and Polish immigrants in 21 states raised money to bring nine students from Poland to study at universities such as Harvard, Yale, and Columbia and to send an American professor to the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. Seeing the impact of his work, Mizwa gave up his doctoral studies at Harvard and his professorship to focus on educating Poles.

With the 150th anniversary of Kosciuszko’s arrival in America approaching, Mizwa sought to create “a living memorial to Tadeusz Kosciuszko.” He wrote an appeal to 40 Polish newspapers, 800 Polish pastors, and Polish-American organizations to start “an Endowment Fund to make it possible for future generations in reborn Poland to study in America and learn something about the nation for whose freedom Kosciuszko fought. And, it would make it possible for young Americans to study in Poland and learn something about the nation which produced Kosciuszko.” Newspapers ran the appeal. Still, Polonia’s leaders responded that Mizwa was “the wrong man, with the wrong idea, at the wrong time.” Of the 800 Polish pastors, only one replied that it was “a good idea.”

When Mizwa turned to Americans to raise $1 million for an educational endowment, he was told it was “a pipe dream.” But, he persuaded Dr. MacCraken to become the first President of the Foundation and Vauclain and other Americans to serve on the Board of Trustees. He convinced the Polish Consulate in New York on Third Avenue and 57th Street to give him a room for an office.

In 1925, The Kosciuszko Foundation, Inc., was incorporated in New York to raise funds to grant financial aid to deserving Polish students to study in America and American students desiring to study in Poland; to encourage and aid the exchange of professors, scholars, and lecturers between Poland and the United States; and to cultivate closer intellectual and cultural ties between the two countries. Initially, $43,575 was raised for the Foundation, primarily by Americans, with $250 coming from a Polish professor. Polonia was skeptical of his efforts. But, Mizwa wrote in his memoirs, “I had the perseverance of a Polish peasant, the enthusiasm of a fanatic, and the belief that sooner or later, $1 million would be raised as an endowment fund.”

Mizwa pressed on and, in 1927, persuaded Maria Skłodowska Curie, the Polish Nobel Prize-winning chemist and physicist, to allow him to name a scholarship after her. With the support of Madame Curie, people began to take notice. The 1929 stock market collapse made fundraising more difficult, but Mizwa spent the next 20 years traveling the country to Polish-American communities from New Hampshire to Nebraska and Wisconsin to Florida. He passed around a hat to collect dimes, quarters, and dollars for scholarships each time he spoke.

Mizwa wrote to the editor of a black newspaper telling him that in 1798 Kosciuszko had donated his General’s salary from the American Revolution to the emancipation of African slaves. The editor urged teenagers from the Billkens Club to send dimes to the Kosciuszko Foundation as a token of appreciation for Kosciuszko’s efforts to free the slaves. Nearly $100 in dimes from black children came in, and Mizwa wrote: “This had more moral value in stimulating interest than the amount of money raised.”

The Annual Dinner & Debutante Ball

In 1928, the Kosciuszko Foundation hosted a dinner at New York’s Commodore Hotel to honor Paderewski, and by 1933, the Foundation began holding an annual fundraising ball to support its operations. The first ball was held at the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York and moved to the luxurious Waldorf=Astoria in 1936. By 1941, debutantes were presented, and young women aged 16 to 25 with a background of academic achievement were invited to participate. The young ladies are accompanied by their fathers, West Point Cadets, or midshipmen from the Kings Point Merchant Marine Academy. The debutantes are presented to society before an audience of diplomats, community leaders, and other notables.

World War II

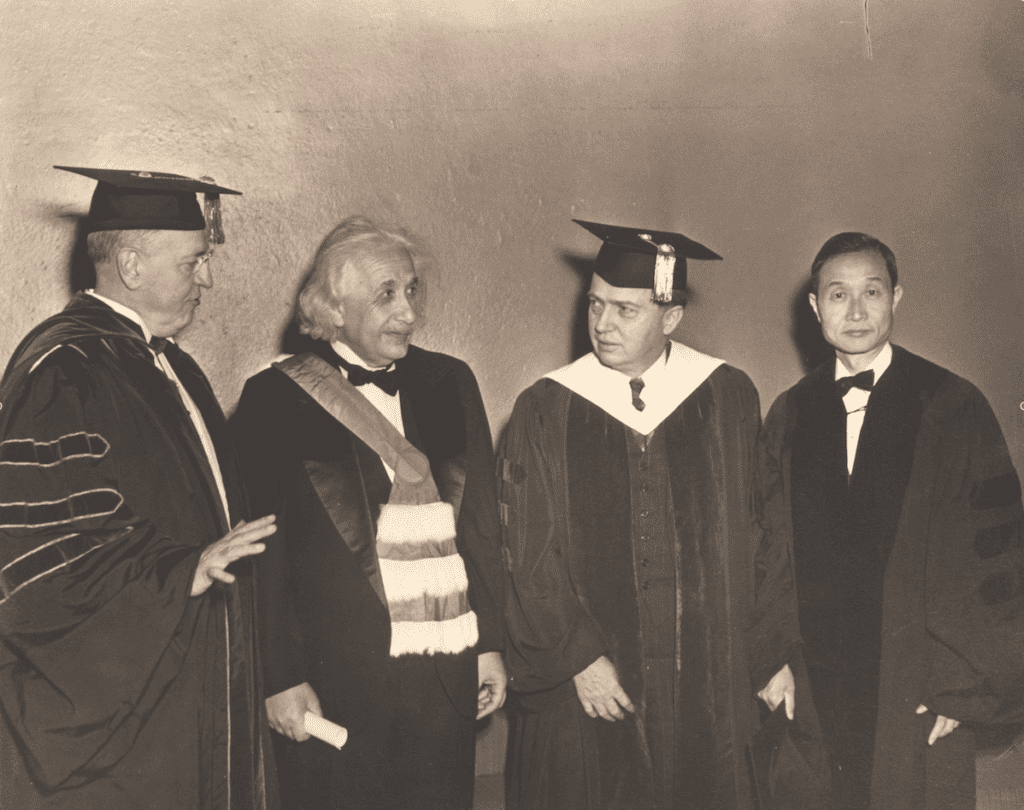

When Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia attacked Poland in 1939, the exchange of scholars between the United States and Poland was cut off. During the war, Mizwa sent relief aid to Poland via back channels. More than 800 Polish soldiers and refugees were interned in Switzerland, and Mizwa sent half of the foundation’s funds to educate these soldiers. And with Polish soldiers training in Edinburgh, Scotland, to prepare for the invasion of Normandy, Mizwa raised funds to send medical books and journals to Polish students stationed with them. With Poland under fascist and communist occupation, the Foundation promoted Polish culture and Polish issues in the United States. In May 1943, on the 400th Anniversary of the death of Nicholas Copernicus, the Kosciuszko Foundation held a series of lectures and commemorative programs, including one at Carnegie Hall, at which Albert Einstein was the principal speaker.

The Van Alen Mansion becomes the Kosciuszko Foundation House.

After World War II, Mizwa searched for a permanent headquarters. He looked at 150 buildings before finding the Van Alen mansion, built in 1917. In 1920 it was purchased for $275,000 by Rufus L. Patterson, the owner of American Machine & Foundry. After Patterson died in 1944, his widow, Margaret, put the mansion up for sale the following year. The asking price was $250,000. Mizwa explained that he wanted to buy the mansion for cultural purposes and bargained with Mrs. Patterson for six months. In an incredible act of charity, she lowered the price to $85,000. The foundation made a $10,000 down payment and mortgaged the rest. Over the next several years, Mrs. Patterson donated another $16,000 to the Kosciuszko Foundation to help pay off the mortgage.

Mizwa’s deal with Mrs. Patterson was the most outstanding achievement in the Foundation’s history because it gave Polonia a headquarters in the most affluent and desirable neighborhood in New York. Mizwa had finally won Polonia’s trust, and they joined the Foundation and contributed to scholarships and cultural programs.

In 1950, Stanislaw Petera, a retired worker from General Electric, met with Mizwa to explain that his last will would leave $25,000 in government bonds to the foundation. He wanted to donate the money sooner to honor the Foundation’s 25th anniversary. Petera’s attorney created a living trust, which gave his assets to the foundation. The money was invested in stocks, and Petera received a 2.5% yield to cover his living expenses while the Kosciuszko Foundation paid off its mortgage. It was a brilliant act of charity that benefitted Petera and Polonia.

The Gallery of Polish Masters

With the Kosciuszko Foundation’s headquarters in the shadow of the world’s most prestigious art collections – Manhattan’s Museum Mile on 5th Avenue, Polonia had the perfect place to exhibit paintings by Poland’s finest masters. Mizwa raised money to purchase and acquire donations of paintings by Polish masters such as Matejko, Chełmonski, Malczewski, Kossak, Brandt, Styka, and others that today fill the gallery on the second floor of the Kosciuszko Foundation. It is open to the public that comes to the Upper East Side to visit art museums.

The Chopin Competition 1949

The Kosciuszko Foundation Chopin Piano Competition was established in 1949 in honor of the hundredth anniversary of the death of Frederic Chopin. The inauguration occurred at the Kosciuszko Foundation with Witold Małcużyński as a guest artist. By unanimous decision, the first winner was a 20-year-old black student named Roy Eaton, who later became a composer and teacher at the Manhattan School of Music. Mizwa proudly proclaimed that “Kosciuszko’s will of 1798 was partly carried out.” Over the years, renowned musicians such as Van Cliburn, Ian Hobson, and Murray Perahia have won the competition. Today the annual Chopin Competition continues to encourage gifted young pianists to further their studies and to perform the works of various Polish composers.

Mizwa becomes President

After serving as the visionary, backbone, and chief executive officer for three decades, in 1955, Mizwa became the second President of the Kosciuszko Foundation, taking over from Prof. MacCraken. Poland was suffering under Russian occupation and Communism. Yet, Mizwa kept alive the intellectual exchange between Poland and the United States through projects such as the “Books to Poland” campaign to restore university libraries. The Communists made life difficult for Poland and the Foundation during the late 1940s and 50s. Passports for Polish scholars to travel to the west were hard to come by, and Mizwa bemoaned the student exchanges writing, “There have been lights and shadows, but the shadows have begun to deepen.” More scholarships were given to Polish Americans and Poles already in the United States.

The Kosciuszko Foundation Dictionary

In 1959 the Kosciuszko Foundation published its indispensable English-Polish dictionary, and in 1961 by, a Polish-English volume. Over the past four decades, it has set the standard on both sides of the Atlantic. It has been reprinted 13 times, most recently with a CD-ROM and DVD versions that can operate on Windows and Macintosh with recordings of all basic English and Polish word forms.

The First Million is the Hardest

People scoffed at Mizwa when he set out to raise a $1 million endowment so that interest could fund scholarships and operations. On June 30, 1969, the Kosciuszko Foundation’s audit report showed that the capital fund amounted to $1,029,248. Mizwa’s vision and hard work had paid off. In 1967, the Board of Trustees approved the notion of local KF chapters across America to help the foundation coordinate its efforts to promote Polish culture across the United States. At the end of 1970, after being the driving force behind the foundation for 45 years, Mizwa stepped down as president, quoting the Apostle Paul, said: “I have fought a good fight. I have finished my course. I have kept my faith.” Mizwa died the following year.

The Vision Lives On - Eugene Kusielewicz.

In 1971, Mizwa’s assistant, Dr. Eugene Kusielewicz, an associate professor of History from St. John’s University, became President. Kusielewicz was a noted authority on Woodrow Wilson and the Polish cause at the Paris Peace Conference. He began a program to train Polish-American physicians and reestablish the summer sessions. In the 1970s, he sent more than 2,500 American students to Krakow, Lublin, and other language programs in Poland. These Americans became ambassadors of freedom and democracy. The exchange of scholars from Poland to the United States also picked up, which for some, was controversial because Poland was still behind Iron Curtain. But like Mizwa, Kusielewicz believed that exposing Polish scholars to American democracy and capitalism would help bring down Communism.

The 1970s were the low point of the era of Polish jokes in America, and when a young Polish reporter, Thomas Poskroposki, was told that he had to change his “Pollack” name if he wanted to get a job at the New York Daily News, he changed it to Thomas Poster. This motivated Kusielewicz to speak up about discrimination against Poles. Educating Polish Americans proved to be the best tool in his arsenal. In 1973, the Kosciuszko Foundation commissioned Henryk Gorecki to compose the Copernican Symphony Number 2 to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the birth of Nicholas Copernicus. The symphony premiered at Carnegie Hall.

Cardinal Karol Wojtyła visits the Kosciuszko Foundation

On Sept. 4, 1976, Cardinal Karol Wojtyła visited the Kosciuszko Foundation and told its members that foundation work is “vital at this time. We realize that culture creates a national identity and ultimately creates the nation itself.” Cardinal Wojtyła, who became Pope John Paul II two years later, praised the work of “The Kosciuszko Foundation, ” which attempts to serve the interests of the Polish people diligently. We must be grateful to everyone who has contributed to these efforts and those who continue to work towards these goals. This work is one of the greatest components of our national identity.”

Honorary Trustees

Over the years, the Kosciuszko Foundation has added honorary trustees to its board, such as Zbigniew Brzezinski, Czeslaw Milosz, Andrzej Wajda, Krzysztof Penderecki, and also provided medals of recognition to people such as Artur Rubinstein, Norman Davies, Ryszard Kapuscinski, Rafal Olbinski, Dr. Maria Siemionow, and other distinguished Poles who have performed or lectured at the foundation. This elaborate network has been part of the foundation’s success.

Albert Juszczak – Solidarity Turns Poland Right Side Up

Dr. Albert Juszczak became President of the Kosciuszko Foundation in 1979, just in time to witness the Solidarity era, the most tumultuous years in Poland since World War II. As a Polish language and literature teacher, he focused on academics and scholarships, interested in solidifying the status of Polish intellectual life at the Kosciuszko Foundation. During martial law, the Polish military regime that cracked down on Solidarity tried to keep out any Western influence, Juszczak kept opening the doors to universities in Poland when they needed American support the most.

In 1984, The Kosciuszko Foundation sponsored a national tour for Wladyslaw Bartoszewski, who traveled across the country lecturing on Polish-Jewish relations during World War II. Bartoszewski was a soldier in the AK, the Polish underground, and co-founder of Zegota, the Council for Aid to Jews. He also organized assistance for the participants of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising of April 1943 and invited Jan Karski to speak at the Foundation.

Joseph E. Gore and a New Poland

As an attorney, Joseph E. Gore brought a new set of skills to The Kosciuszko Foundation Presidency in 1987. He expanded the Foundation’s By-Laws, rules, and regulations, opened new KF chapters across the country, and reinstated the National Advisory Council to help carry out the foundation’s mission. Gore oversaw a $1.5 million renovation of the mansion and established a rental program to offset growing operational expenses. He also prepared legal donor fund agreements and persuaded donors to establish six new funds, the first being the Zelosky Trust from First Chicago.

The collapse of Communism provided new opportunities for the Foundation, and Gore established a Warsaw office and negotiated office space with the University of Warsaw. He created American and Polish Advisory Committees of professors and scholars to improve the selection process for scholarships and grants during the annual interviews of the Exchange Program candidates in Poland. He established a relationship with White & Case, one of the world’s largest law firms, to provide legal work for the Foundation on a pro bono basis.

Gore entered into agreements with the Alfred Jurzykowski Foundation of New York and the AGH University of Science and Technology to help establish a Department of Environmental Sciences. The two NY foundations committed $100,000 annually for ten years to be used by AGH to purchase scientific equipment and technical engineering books; support faculty and students exchanges to and from the USA.

Under Gore’s direction, the long-running monthly Chamber Music Series was established and broadcast on WQXR-FM. He also reinstated the Marcella Sembrich Vocal Scholarship Competition. While tens of thousands of art connoisseurs have viewed the art collection over the years, Gore published a glossy catalog, “The Polish Masters from The Kosciuszko Foundation Collection,” which is now in libraries and coffee tables around the world. And while the KF dictionary was first published in 1959, and Gore revolutionized the dictionary, updating the text and providing computerized versions for PCs and Macintosh.

Alex Storozynski & New Challenges for the Kosciuszko Foundation

In November 2008, Alex Storozynski, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of the award-winning biography of Kosciuszko, “The Peasant Prince,” was elected President of the foundation. While in the 70s, Poskroposki had to change his name to work at the Daily News; by the 90s, in that same newspaper, Storozynski was proud to have his byline over stories about Kosciuszko, Andrzej Wajda, and other Polish issues. The son and grandson of decorated World War II soldiers, he honored Polish veterans at the Kosciuszko Foundation with films, author’s evenings, and photo exhibits about their struggle to free Poland.

Storozynski invited the President of the National Bank of Poland, Sławomir Skrzypek, for a networking session at the Foundation with Polish bankers from Wall Street to discuss Poland’s economy. In 2009, he negotiated the donation of a new building to the foundation, this one in Washington, D.C. He organized an international conference about the Katyn massacre at the Library of Congress in Washington, attracting speakers such as Dr. Brzezinski and members of the United States Congress, and persuaded the U.S. Senate to show an exhibit by historian Andrzej Przewoznik in the rotunda of the Senate office building.

Storozynski modernized the foundation’s website kf.org, added a Facebook page, and wrote a petition asking newspapers to stop using the phrase “Polish concentration camps.” So far, hundreds of thousands of people have signed it, including President Bronisław Komorowski, Norman Davies, members of the U.S. Congress, Chief Rabbi of Poland Michael Schudrich, Christian and Jewish survivors of Auschwitz, and many other renowned people. As a result of the petition, The Wall Street Journal and The San Francisco Chronicle have promised to stop using this historically erroneous phrase.

Thanks to Alex Storozynski, The Kosciuszko Foundation has now legally registered in Poland as – Fundacja Kościuszkowska Polska, which allows Polish citizens to receive tax deductions for donating money for scholarships and the promotion of Polish culture. He also spearheaded the merger of the American Council for Polish Culture in Washington, DC.

He is now President Emeritus, Trustee, and Chairman of the Kosciuszko Foundation.

John S. Micgiel and Today’s Kosciuszko Foundation

In April 2014, the Foundation’s Board of Trustees unanimously elected its seventh President, Dr. John S. Micgiel of Columbia University. Dr. Micgiel taught for twenty-five years at the University’s School of International and Public Affairs, where for many years he directed the Institute on East Central Europe, the East European, Russian, and Eurasian National Resource Center, and several other Institutes and Centers. He was also on the faculty of Warsaw University’s Eastern Studies Center and the Estonian School of Diplomacy in Tallinn. Professor Micgiel was instrumental in organizing the campaign to raise an endowment valued at $6 million for a newly-filled Professorship in Polish Studies in Columbia University’s History Department.

Micgiel’s priorities were to increase scholarships by ten percent, to embark on an ambitious art conservation and building restoration project, and to move the Foundation’s Warsaw office into more modern and prestigious facilities.

A Vision for Tomorrow

In the 18th century, Tadeusz Kosciuszko said, “By nature, we are all equals – virtue, riches, and knowledge constitute the only difference.” Education is the key to success, and Kosciuszko dedicated his life to the liberation and education of the underprivileged. He also donated his last will to the education of peasants and slaves. In the 20th century, another virtuous Pole, Mizwa, followed his example and established the Kosciuszko Foundation, whose primary mission is education and promoting Polish culture.

As the years rolled on and the challenges facing Poland changed with the times, the Foundation’s work has evolved to meet those challenges. Mizwa started the Foundation after Poland’s rebirth, but his mission took on new meaning during Nazism, Communism, and the Cold War. Today, Poland is once again free and part of NATO and the European Union. Many Kosciuszko Foundation alumni have taken part in that transformation.

These days, young Poles and Polish Americans are uniquely poised to change the world through the humanities and the arts, the sciences, technology, and business. But it takes money to finance their dreams through education. With scholarships, they can become the leaders of tomorrow. For the 21st century, the Kosciuszko Foundation wants to build on the examples set by Kosciuszko and Mizwa, but we need your help to do it.